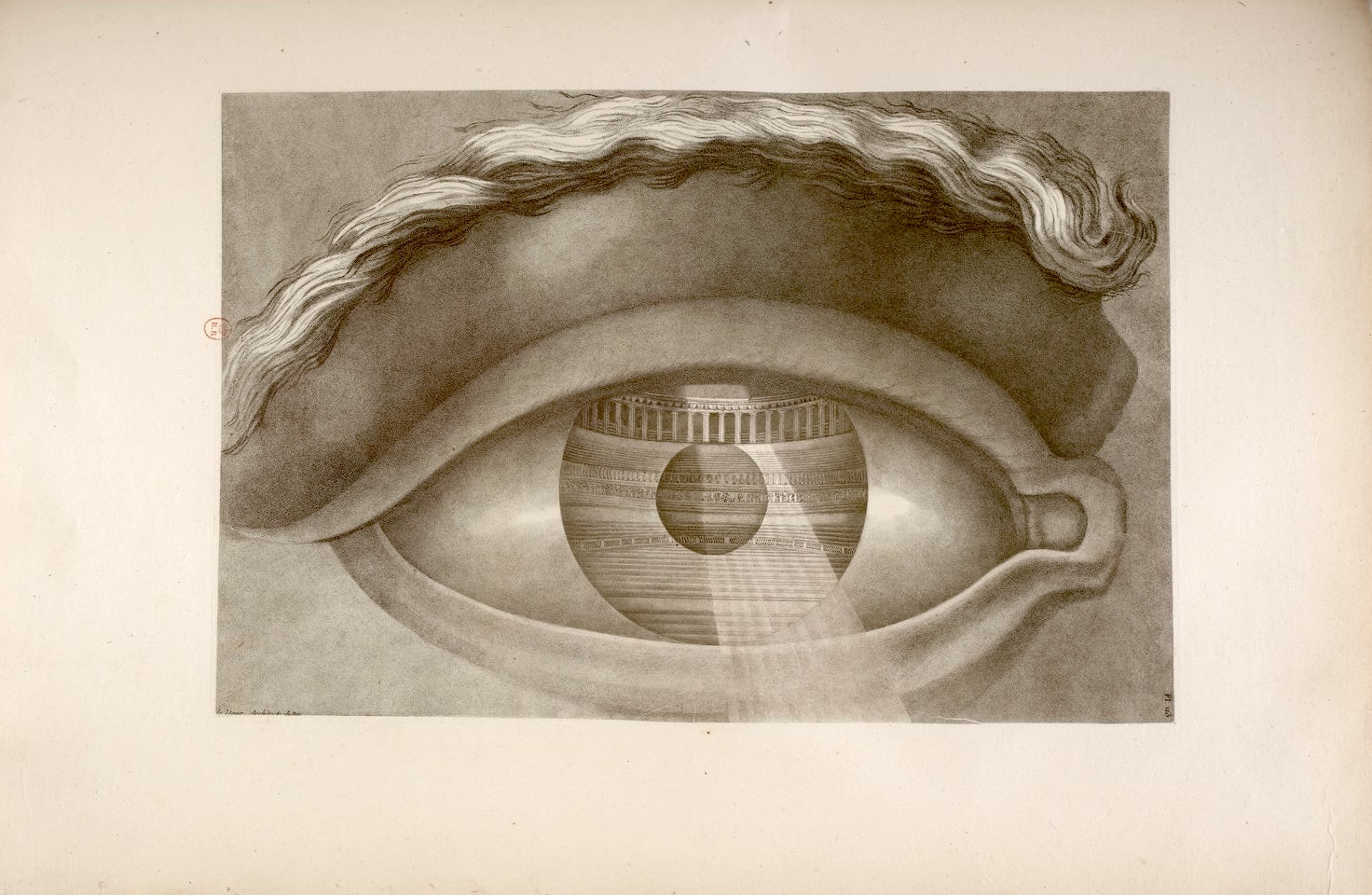

The Théâtre de Besançon Reflected in an Eye (1804). An etching from Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s L’architecture considérée sous le rapport de l’art, des moeurs et de la législation, capturing the Théâtre de Besançon within the human eye. This image embodies 18th-century France’s evolving vision—both literal and intellectual—as Newtonian optics reshaped the way architects like Étienne-Louis Boullée imagined space, light, and monumentality.

Why is it considered “good” to keep people’s attention hostage?

As designers, we’re increasingly at the forefront of an attention-driven world. Lately, I’ve noticed that good design is often described as something extremely easy to use, with minimal friction. It’s about crafting experiences that are so innovative and captivating that users won’t—or can’t—stop engaging. The goal seems to be to capture attention for as long as possible.

Some even say that attention is the new oil or gold, turning UX design into an attention mine, with design practitioners acting more and more like attention miners or dopamine dealers.

But here’s the thing: the definition of good design is always changing.

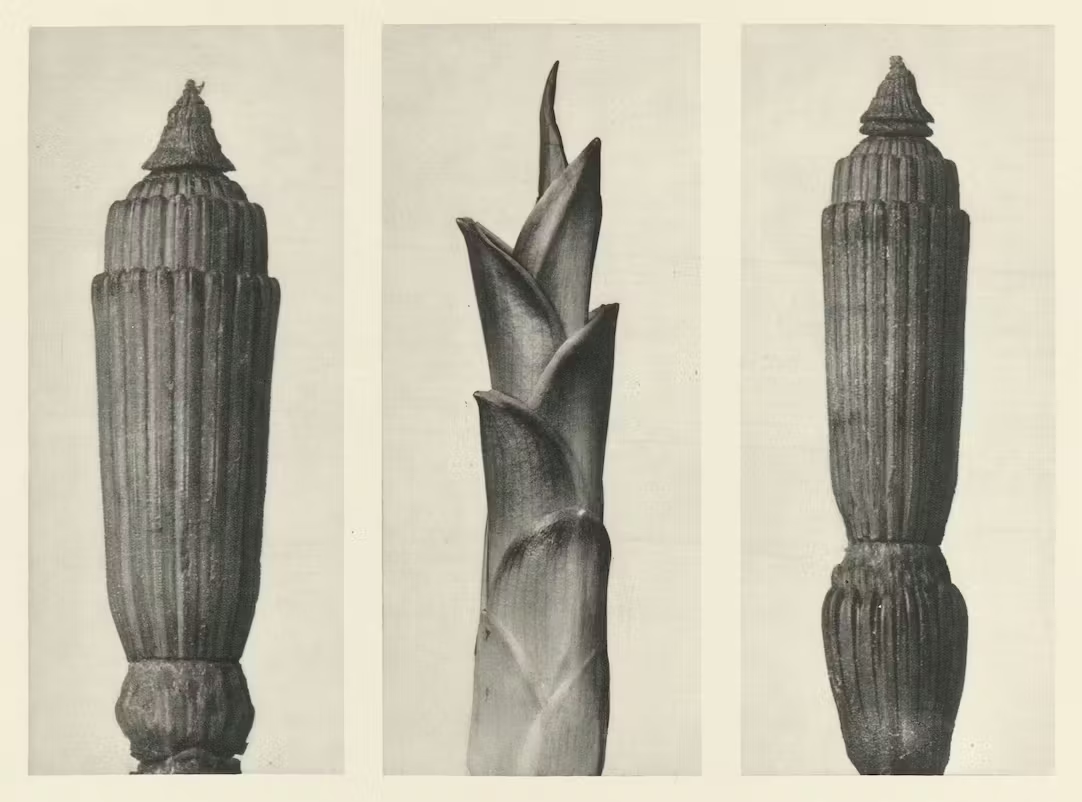

Karl Blossfeldt’s Urformen der Kunst (1928). Blossfeldt’s photographs of plants reveal an unseen world of natural patterns, transforming botanical forms into abstract designs. His work, aligned with Weimar Germany’s avant-garde, captured what Walter Benjamin called the “optical unconscious”—a realm of detail and structure made visible only through the camera’s lens.

In the 19th century, good design was about making production easier, driven by the rise of industrialization. Ornament was pushed aside in favor of simplicity and efficiency—William Morris and Adolf Loos famously debated this shift. Back then, designing well meant reducing not only material friction but also economic, functional, and social friction.

This fascinating read by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley dives into how design shapes our understanding of what it means to be human. They take you on a journey through the history of architecture and design, sparking thoughts about our identity as a species and our relationship with the built environment. Design essentially designs humans, as they aptly put it.

Fast forward to the mid-20th century, and good design evolved to meet the needs of modernism. Designers embraced smooth surfaces, like those Le Corbusier used in his architecture to “calm the nerves shattered in the aftermath of war.” The focus was once again on eliminating friction and discomfort—both psychological and physical—offering an anesthetic sense of relief from past trauma.

What’s clear is that good design has always been shaped by the dominant ideals and needs of the time (Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley beautifully capture this in one of my favorite books of all time, Are We Human?). So, defining it in any fixed way is nearly impossible. What we can do is constantly question it, recognizing the underlying ideologies that shape it, especially when the current definition often involves capturing attention at all costs.

Which leads me to wonder: why is it considered “good” to keep people’s attention hostage?

What if we, as designers, shifted the goal from capturing attention to liberating it? Wouldn’t that be good?

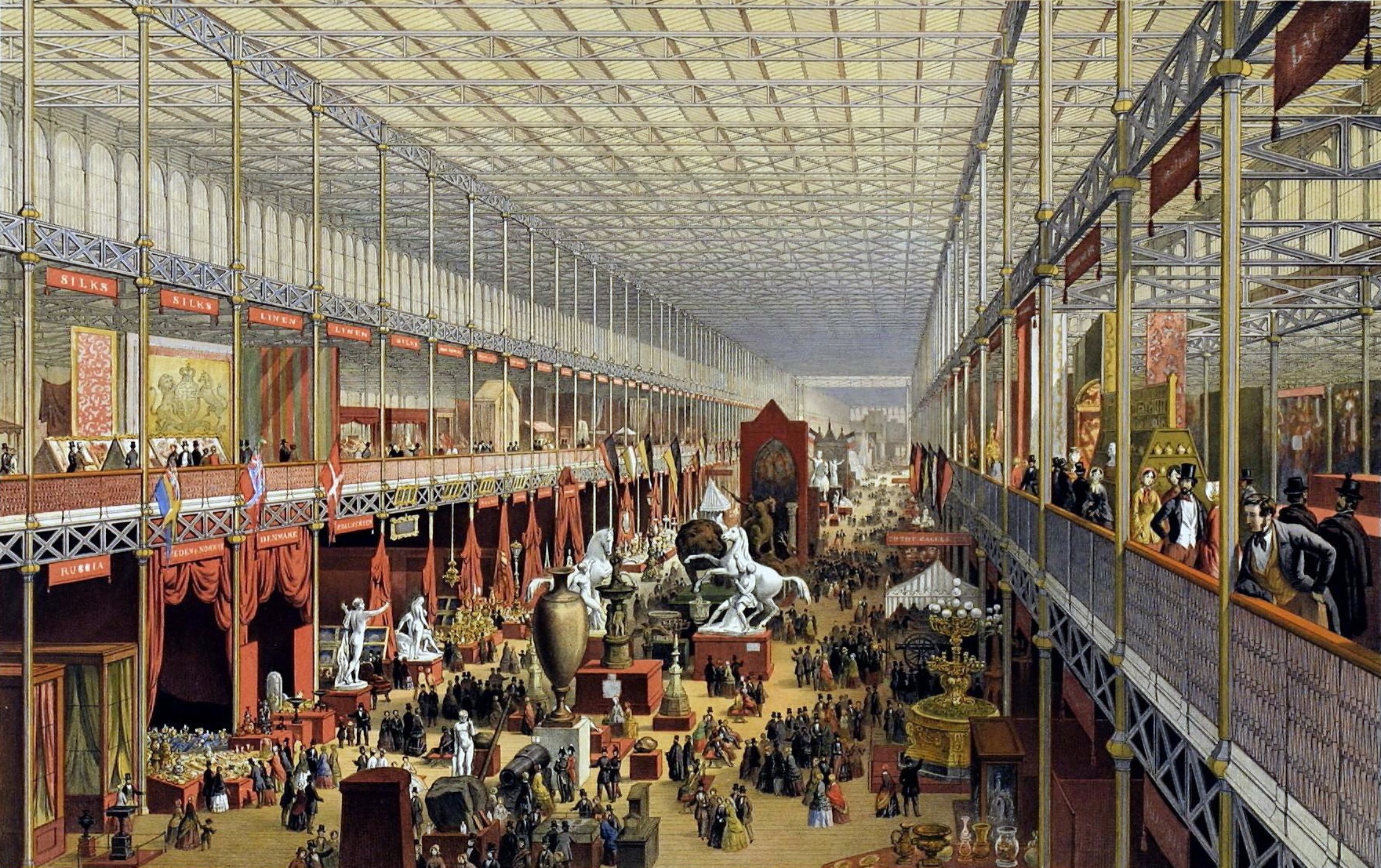

The Crystal Palace and the Triumph of Industry (1851). The vast iron-and-glass interior of the Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition of 1851, symbolized Britain’s industrial dominance. A showcase of modern technology and design, it influenced thinkers like Adolf Loos, who admired English utilitarianism—objects stripped of ornament, shaped by necessity rather than embellishment.